"Nir's Weekly Torah Portion" - Parashat Terumah

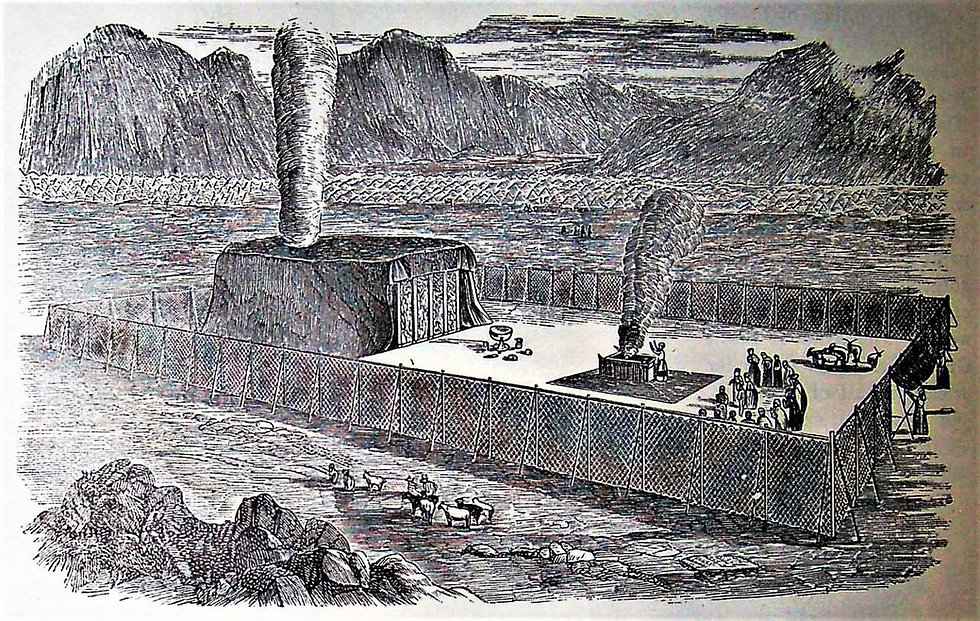

Parashat Terumah is the seventh weekly portion in the Book of Exodus, beginning with Chapter 25, verse 1, and ending with Chapter 27, verse 19. The portion deals with the very detailed instructions given to Moses for building the Tabernacle and how to finance its construction. In the first stage, before entering the land and establishing permanent settlement, there would be a temporary Tabernacle made primarily of wooden boards and curtains from animal skins. This way, the Israelites would be able to dismantle the Tabernacle and rebuild it throughout their journeys in the desert.

But why is a Tabernacle for God needed at all? Isn't God present everywhere? Isn't everything one? What is the connection between a physical place and spirituality? This issue has occupied and continues to occupy many commentators.

According to one approach (the "Documentary Hypothesis"), Parashat Terumah reflects the interests of the Priestly source (P), whose purpose was to establish the status of the priesthood as the exclusive mediator between the people and God. This is a critical research perspective of the Bible that sees in the meticulous details of the Tabernacle a reflection of a political-religious struggle between different power groups during the formation of the biblical text.

Yehezkel Kaufmann, an Israeli biblical scholar, saw in the details of the Tabernacle evidence of the religious-historical development of the monotheistic concept. According to Kaufmann, the Tabernacle represents an intermediate stage in the development of Jewish religious thought – a stage that preserves physical elements from the pagan world but disconnects them from the perception of divinity as multiple and having physical needs.

A similar perspective reflecting deep psychological insight can be found in Rashi's commentary on why a Tabernacle is needed at all. Rashi understands that the Bible deals with a basic human need – the need for tangible representation of the most abstract ideas. In this reading, the Torah does not ignore human psychology but adapts itself to it.

According to this view, despite prohibitions, humans will always create physical objects for themselves which they will sanctify. And if this is the working assumption, then let's at least minimize damage.

The philosopher Martin Buber offered an interesting interpretation of this paradox. According to Buber, the dialectic between the spiritual and the material is precisely the essence of Jewish religiosity. The Tabernacle is not just a compromise with human desire but an expression of the belief that holiness must be realized in the concrete space of life. In this context, it is interesting to note that the verse says "I will dwell among them" (וְשָׁכַנְתִּי בְּתוֹכָם) and not "in it" – a hint that the true purpose is not the dwelling of the Divine Presence in the physical structure but within the people themselves.

From a contemporary sociological perspective, Parashat Terumah can be seen as an expression of the constant tension between the religious establishment (represented by the priests and the Tabernacle) and personal, direct spirituality. This is a tension that accompanies Israeli society to this day – between institutionalized religious establishments and more personal and free expressions of spirituality.

Parashat Terumah, in a critical reading, invites us to think about the place of physical structures and material symbols in spiritual and community life today. Do the buildings and institutions we have built serve the human spirit, or have they become an end in themselves?

As a ltour guide, I see how archaeological sites and religious buildings continue to serve as meeting points between past and present, between the spiritual and the physical. Perhaps this is the profound lesson of Parashat Terumah: not the recognition of the human need for physical places of holiness, but the understanding that these structures are only means, and that true holiness dwells "within them" – within human beings themselves.

Image: The Tabernacle. Illustration from the Holman Bible, 1890